Among the Native American cultures of the northeastern woodlands, the longhouse was more than a structure it was a way of life. Both the Algonquian and the Iroquois peoples made use of longhouses, although the Iroquois are more famously associated with them. These dwellings were not just shelter; they were the center of social, political, and family life. Built from natural materials found in the forests, the longhouse embodied cooperation, extended family living, and a close connection to the land. Understanding how the Algonquian and Iroquois longhouses were constructed and used gives deep insight into their cultures, values, and daily lives.

Design and Structure of the Longhouse

Construction Materials

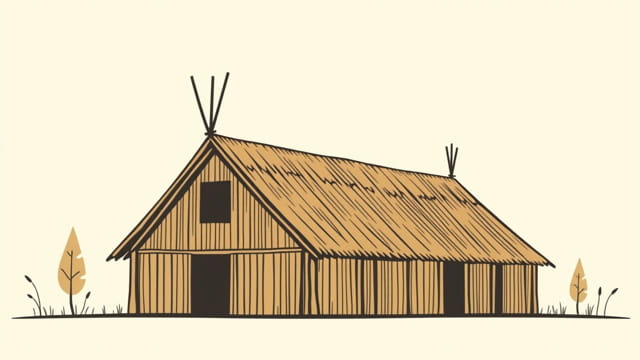

Longhouses were built primarily using wood and bark. Tall wooden poles formed the framework, while slabs of elm or cedar bark were lashed to the outside to form the walls and roofing. The structure was rectangular, often over 20 feet wide and up to 100 feet long, depending on the number of families it housed.

These buildings were expertly adapted to the northeastern climate. The overlapping bark acted as insulation, and the curved roof helped snow slide off during harsh winters. Each end of the longhouse was rounded to reduce wind resistance and improve structural stability.

Internal Layout

Inside the longhouse, space was carefully organized. A central hallway ran the length of the structure with small compartments or alcoves along both sides. These compartments were living areas for nuclear families. Raised platforms were used as beds or storage, and animal skins or woven mats provided insulation and privacy.

Every few feet along the central corridor, there was a fire pit. Each fire was shared by two families, with smoke holes above to allow ventilation. Wooden flaps or bark coverings could be adjusted to manage airflow and protect from rain or snow.

Use of the Longhouse by the Iroquois

Social Structure and Communal Living

The Iroquois longhouse was more than a home; it symbolized the clan system that governed Iroquois society. Each longhouse was typically inhabited by members of a matrilineal clan, meaning descent and inheritance were traced through the mother. A single longhouse might shelter 20 or more people, often related women with their husbands and children.

Clan mothers, the oldest women of the clan, held significant power. They chose the male leaders, known as sachems, and managed property and agricultural activities. This female-centered social structure was reflected in the longhouse’s organization.

Political and Ceremonial Role

The Iroquois Confederacy, also known as the Haudenosaunee, saw the longhouse as a metaphor for unity. The term longhouse was even used symbolically to describe the entire confederation, which united five (later six) nations under a common government.

Some longhouses served political or ceremonial functions. Clan meetings, naming ceremonies, and religious rituals often took place within their walls. The communal nature of the longhouse made it a natural setting for group decision-making and storytelling traditions.

Everyday Activities

Daily life in the Iroquois longhouse included food preparation, crafting, and child-rearing. Women tended to gardens of corn, beans, and squash outside the structure, while inside they cooked meals over shared fire pits. Men often returned from hunting or warfare to the longhouse, which served as their place of rest and reintegration.

Children learned from watching adults and were taught oral traditions, games, and survival skills in the communal space. Craftwork like basket-weaving, beadwork, and tool-making also took place within the longhouse, especially during the long winter months.

Use of the Longhouse by the Algonquian Peoples

Differences in Longhouse Design

While the Iroquois are more closely associated with the longhouse, some Algonquian tribes also built similar structures, though their primary dwellings were often wigwams dome-shaped huts. However, in certain regions or during communal gatherings, longhouses were constructed and used.

Algonquian longhouses tended to be smaller and less permanent. These structures were often seasonal, used during periods of community activity such as festivals, trading, or political meetings. They were built using flexible saplings covered with bark or mats and often dismantled when not needed.

Community Functions

For Algonquian groups, longhouses sometimes served as multi-family dwellings, but more often, they had communal or ceremonial uses. Councils, spiritual rituals, and gatherings for storytelling or feasting were held inside these buildings. The interior layout was more flexible and adapted to temporary usage rather than long-term domestic life.

Because many Algonquian tribes were semi-nomadic, their use of longhouses was often part of a seasonal cycle. Tribes would move between fishing, hunting, and farming areas, erecting longhouses as needed for shelter or gathering.

Symbolism and Cultural Importance

The Longhouse as a Cultural Symbol

For the Iroquois, the longhouse was a powerful metaphor. The confederacy itself was often described as a great longhouse stretching across the land, with each nation representing a door or wing. The idea of unity through shared space was deeply embedded in their worldview.

This symbolism extended to diplomacy. The Great Law of Peace, which governed the Iroquois Confederacy, used longhouse imagery to explain concepts of balance, cooperation, and respect among the nations.

Spiritual Connections

Both Iroquois and Algonquian traditions viewed the longhouse as a sacred space. The fire at the center of each family’s space was a spiritual focus, connecting them to their ancestors and the Creator. Ceremonial chants, dances, and offerings were performed around these fires during important events.

Dreams and visions, important to many Native American belief systems, were also shared and interpreted within the longhouse. The communal environment helped reinforce cultural identity and spiritual unity.

Preservation and Modern Recognition

Historical Reconstruction

Today, reconstructed longhouses can be found at cultural heritage sites and museums across North America. These recreations serve as educational tools, offering insight into indigenous engineering, social organization, and traditional lifestyles.

Longhouse replicas are often used during festivals and by indigenous educators to teach youth about their ancestral heritage. They stand as symbols of resilience and cultural pride among Native American communities.

Continued Cultural Importance

While modern housing has replaced traditional longhouses in most communities, the concept remains alive in ceremonies, language, and governance. Longhouse ceremonies, including condolence rituals and seasonal celebrations, are still practiced among the Haudenosaunee and some Algonquian groups.

Efforts to preserve indigenous languages and customs often involve referencing the values embodied by the longhouse cooperation, respect for elders, and harmony with nature.

The Algonquian and Iroquois longhouse was far more than a dwelling; it was a vital part of cultural identity and community life. For the Iroquois, it was the center of social and political structure, while for some Algonquian groups, it played a role in seasonal and ceremonial life. These longhouses stood as symbols of unity, tradition, and resilience. Understanding their use and design gives us a richer picture of indigenous innovation and the deeply communal values that shaped Native American societies in the northeastern woodlands.