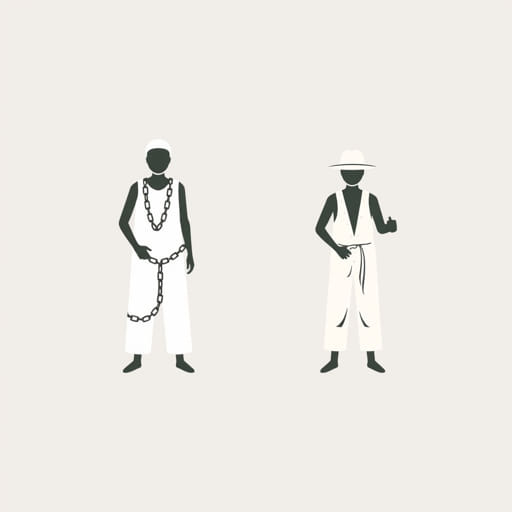

Throughout American history and colonial development, systems of labor have played a defining role in shaping society and the economy. Two distinct forms of labor that emerged at different times and under different conditions were indentured servitude and sharecropping. While both systems relied on laborers working under contracts or agreements, they varied greatly in terms of origin, time period, structure, and long-term impact. Understanding the differences between an indentured servant and a sharecropper reveals much about the evolution of labor and exploitation in both colonial America and the post-Civil War South.

Origins and Historical Context

Indentured Servitude

Indentured servitude began in the early 1600s as a response to the growing demand for labor in the American colonies, especially in agriculture and tobacco plantations. Many poor Europeans, unable to afford passage to the New World, agreed to work for a set number of years (typically 4 to 7) in exchange for transportation, room, board, and eventual freedom. This form of contract labor was especially common in British North America and peaked during the 17th century.

Sharecropping

Sharecropping developed much later, after the American Civil War ended in 1865. With the abolition of slavery, plantation owners in the South had to find a new way to maintain agricultural production. Former slaves and poor whites, often without land or capital, entered into sharecropping agreements. These contracts allowed them to farm plots of land in return for a portion of the crops produced, typically around 50%. However, the economic conditions often left them in cycles of debt and poverty.

Terms of Labor and Contracts

Working Agreements

Indentured servants signed contracts known as indentures that bound them to work for a specific employer for a certain period. These contracts were often legal documents that included conditions of service, rights to food and shelter, and promises of freedom dues at the end of the term, which might include land, money, or goods.

Sharecroppers, in contrast, typically entered into annual or seasonal agreements. These contracts were often informal or deliberately unclear, allowing landowners to manipulate the terms. Since many sharecroppers were illiterate, they had little legal recourse and were vulnerable to exploitation.

Freedom and Autonomy

An indentured servant, although bound by contract, was technically a free person. After completing the agreed-upon service, they were free to pursue land ownership, start businesses, or work for wages. In some cases, indentured servants became prosperous landowners themselves.

Sharecroppers had more theoretical autonomy but less actual freedom. Though not bound by long-term contracts, they were economically trapped. They often had to borrow money for tools, seeds, and basic necessities, leading to crippling debt. Many sharecroppers were legally free but economically bound to the landowners.

Living Conditions and Treatment

Indentured Servants

Indentured servants lived under harsh conditions. They were often overworked, poorly fed, and subject to corporal punishment. Because they were considered temporary labor, some masters had little incentive to maintain their health. Mortality rates among indentured servants, especially during the early years of colonization, were high.

Sharecroppers

Sharecroppers usually lived on the land they worked, often in rudimentary cabins. Their living conditions varied, but poverty was nearly universal. Many lived without proper sanitation, electricity, or access to education. Racial discrimination made conditions especially harsh for Black sharecroppers, who were routinely denied justice or fair treatment.

Legal Rights and Social Status

Rights of Indentured Servants

Indentured servants had limited legal rights, but they could bring grievances to court in some cases. They were recognized as persons under the law, unlike enslaved individuals. Upon completion of their contracts, they regained full legal rights and could integrate into colonial society.

Rights of Sharecroppers

Sharecroppers theoretically had more rights since they were not bound by contracts of servitude. However, systemic racism and lack of enforcement made those rights largely meaningless, especially in the segregated South. Many were unable to seek legal remedies due to their economic status or racial identity.

Economic Outcomes

Post-Servitude Opportunities

Former indentured servants had some opportunity for social and economic mobility. Land was more available in early colonial America, and some were able to acquire property, build businesses, or enter trades. The promise of opportunity was part of what attracted many Europeans to indentured servitude.

Sharecroppers faced far fewer prospects. The sharecropping system was designed to maintain a permanent underclass. Few sharecroppers escaped the cycle of debt, and most lacked the education or resources to improve their situation. Generations of families remained trapped in poverty under this system.

Race and Labor Systems

Racial Dynamics

Indentured servants were initially of various European backgrounds, though some Africans were also indentured early in the colonial period. Over time, the institution of racialized slavery replaced indentured servitude, especially in the South, as plantation owners preferred lifelong, inheritable labor.

Sharecropping was heavily racialized from the start. After emancipation, white landowners sought to retain economic control over newly freed Black populations. While some poor whites also became sharecroppers, the system disproportionately affected African Americans, reinforcing social and racial hierarchies.

Long-Term Historical Significance

Impact of Indentured Servitude

Indentured servitude shaped early colonial labor markets and contributed to the development of American society. Many early settlers began as indentured servants. However, the shift to African slavery in the 18th century marked a turning point in labor practices and racial ideologies in the colonies.

Legacy of Sharecropping

Sharecropping continued well into the 20th century and left a deep legacy of inequality in the American South. It preserved many of the economic conditions of slavery and reinforced a social order built on racial discrimination. The system contributed to the Great Migration, as African Americans moved northward to escape poverty and segregation.

Key Differences Summarized

- Time Period: Indentured servitude was most common in the 1600s and 1700s; sharecropping emerged after 1865.

- Labor Agreement: Indentured servants had set terms; sharecroppers often had open-ended or yearly contracts.

- Freedom: Indentured servants were freed after their term; sharecroppers remained in economic bondage.

- Legal Status: Indentured servants had minimal rights but legal recognition; sharecroppers had rights in theory but not in practice.

- Racial Component: Indentured servitude was less racially defined; sharecropping was heavily racialized.

Indentured servants and sharecroppers both endured systems of exploitation, but they did so in different historical contexts and under different legal and social frameworks. Indentured servitude was a stepping stone for many European immigrants, offering some hope of eventual independence. Sharecropping, on the other hand, was a mechanism of oppression that maintained racial and economic hierarchies long after slavery was abolished. Understanding these distinctions sheds light on the broader evolution of labor systems and the persistent inequalities rooted in American history.